How to go Casting

Published:

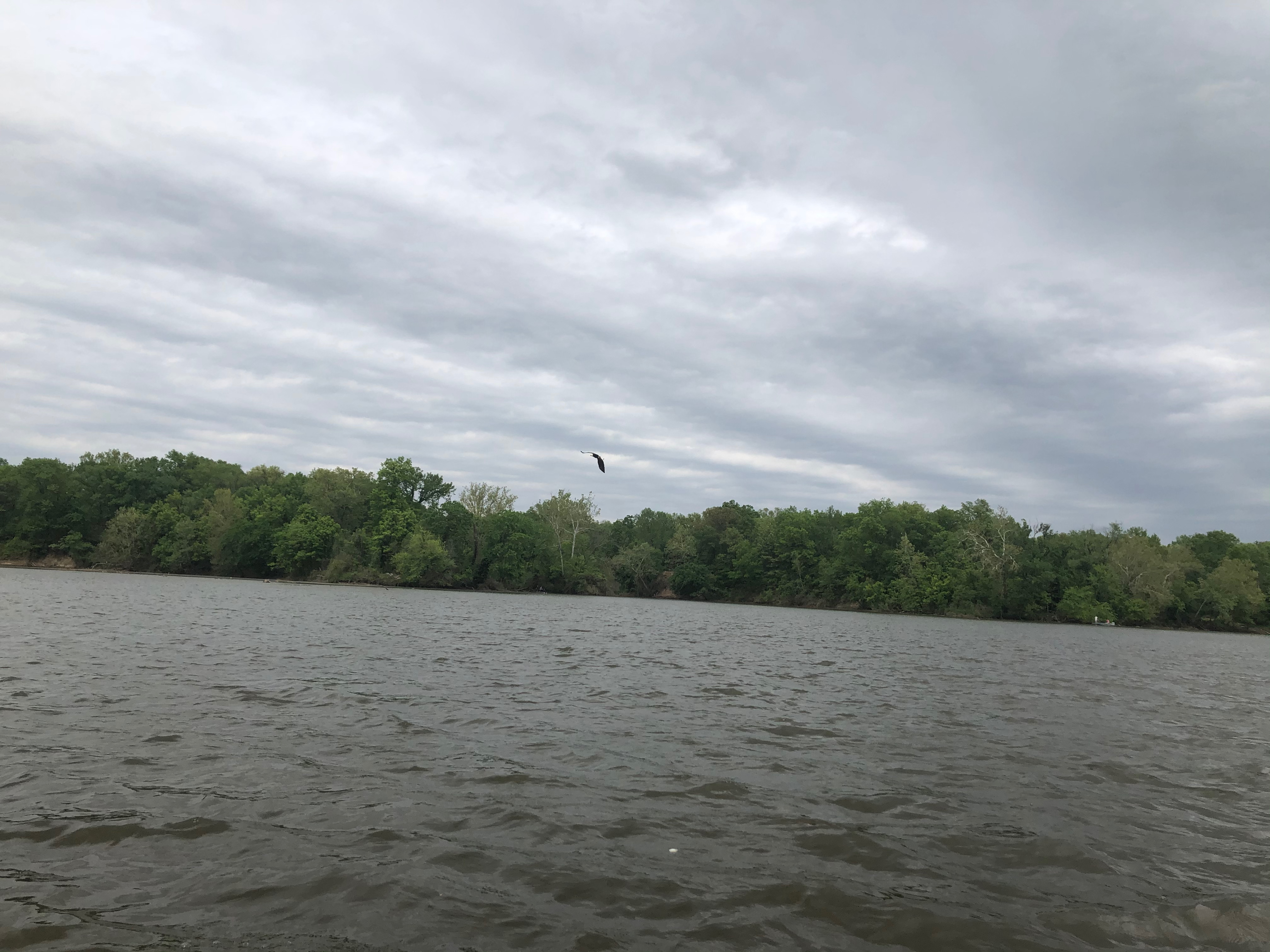

The lake is fifteen minutes from my parents’ house, which makes up for some of its other qualities. Dense thickets and collapsing mud walls encircle the water, interrupted by abandoned camping chairs and a mossy picnic table, which sinks into the Missouri mud. After a rainstorm, the Meramec surges into the lake, depositing Anheuser Busch cans and Marlboro butts all along the shallow cover, where bass like to hide. A thick, foamy film clings to the surface. Mercury levels make the fish not-quite-edible. A park pavillion overlooks the scenery on one end, a boat ramp on the other.

Dad inherited our boat from his brother’s father-in-law. “Tillie,” as the old patriarch dubbed her, comes from modest bass boat stock. She has three wooden benches and an aluminum hull, which tends to amplify our footsteps, scaring the fish away. One bench sports a cool fisher’s swivel chair. Sawed-off PVC pipes serve as fishing-pole holders on the gunnel, which we never use. In her first life, Tillie was better suited to catfishing on the Mississippi, but Dad dislikes the catfish for sport. He fishes for the fight, not the frying pan.

When Dad and I decide to go fishing, usually at an inconvenient time in conflict with the family dinner, we haul Tillie out of Dad’s one-car woodshop-garage and hook her to the Toyata. The whole process takes less than twenty minutes. On the drive, I play hip hop or alt-rock, which Dad sometimes enjoys, until we reach the river valley. Sometimes we talk in the car. Sometimes we wait until we’re out on the water.

The lake, which used to be a quarry, has a strict “no-gas-motor” policy. This means that our humble Tillie, so often the runt in a sea of Bass-Pro-purebreds, is actually the top dog in the midst of canoers and paddle-boarders. She skates effortlessly from cove to cove thanks to a foot-pedal trolling motor, powered by a car battery. Once, Dad hooked up the cables wrong, and we couldn’t figure out why we were having such a hard time getting the boat to go forward. But most of the time, Tillie is the envy of every fishing kayak we pass.

We were once in the same shoes, with less space and greater patience to work with. We caught the same number of fish.

“Any luck?” Dad asks the other fishers.

“Not today. You?”

“Not a bite.”

The lake isn’t well known as any great fishing hole. In fact, the longest running joke in my family is to call it “going casting.” It’s only “fishing” when you catch something.

Instead, Dad takes the opportunity to catch up on my life out of town. He asks about my research and my writing. He mentions he’s been running with my sister. I’ve gotten into bouldering. The counseling practice is looking for a bigger space. A paper that I worked on was just published. He talks about the marriage workshop he taught with Mom and how it went well. I tell him about the woman I’m dating, and did he ever really know what he was doing, at twenty-three? “Not at all,” he says.

Mostly, we just talk.

Over the years, Dad and I have made a game of casting. We like to think it makes us better at fishing, but we haven’t carried out any controlled experiment. The game is simple. As we cruise around with our trolling motor, we cast as close as we can to the shore. The trick is not to get hooked on a branch, which one accomplishes by flicking the wrist and flipping the bail just so. The game stems from our competitive natures, I know, but it also creates a space for long conversations. It results in many snags, few fish, and a great sense of accomplishment.